PIZZAPALS

An exercise in applying the principles of Value Sensitive Design (VSD), PizzaPals was the product of an effort to produce a pizza ordering app that incorporated the values of fun and libertarian paternalism (tldr: freedom of choice mixed with a guiding hand pointing the way to the most beneficial choice.) Could a commercial app combine the need to sell product while simultaneously encouraging smart choices, and be fun to use at the same time?

Tools

Figma, XD, Photoshop

My Roles

Project Manager, Lead Product Designer, Lead UX Designer

Background

Libertarian Paternalism is defined as the freedom of choice coupled with a push towards choosing what a company or institution believes is the best choice for the individual. This concept can be found throughout many modern-day technologies and is an important strategy many companies utilize to influence their customers. For this project, my team utilized the Value Sensitive Design (VSD) process in order to create a pizza ordering mobile application that supports the values of both libertarian paternalism and fun. Through the creation and design of a prototype version of the app (“PizzaPals”), the team was able to identify supportive methods and limitations regarding the ways in which methods of VSD can be used to maintain desired values within a project scope. In the end, the team found direct user input, multiple iterations, and the use of wireframe prototypes to be the most valuable parts of the VSD solution.

We may want to believe that we have free will, but companies are constantly and continuously nudging us along, attempting to influence our choices and purchases. As part of an exploration of this idea, we were tasked to design a pizza ordering application that was informed by two primary values: libertarian paternalism and fun.

Libertarian paternalism supports freedom of choice - a foundational libertarian concept - coupled with a push towards choosing what the company or institution believes is the best choice for the individual. This approach addresses the values of free will, self-control, and human welfare by encouraging stakeholders to make the choice that’s “good” for them while enabling them to make their own choices.

The second value, fun, we defined as an activity or interaction that provides a sense of joy and or excitement, or, to borrow a definition from another team, “something you’d want to do again.” This value, at first blush, may appear to be slightly at odds with a paternalist value – sometimes the “best” choice isn’t the fun choice, but we believe a solution encompassing both values is possible.

Our goal was to create an app that provides a fun way to order pizza while also benefiting the user. We accomplished this by using an approach centered on the notion of “positive nudges,” or encouragement to make better choices as opposed to a negative or shame-based approach. Incorporated into our design are suggestions, behavioral reinforcement through healthy pizza ordering “streaks” and complete insight into the quantitative impact of past pizza order choices. To introduce the element of fun, we created Pepper the pepperoni as our mascot to engage with the consumer and serve as the friendly voice suggesting healthy choices.

Design Process

Value Sensitive Design Methodology

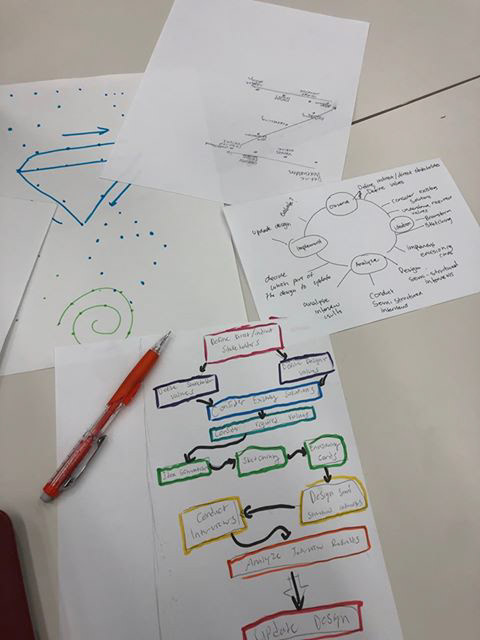

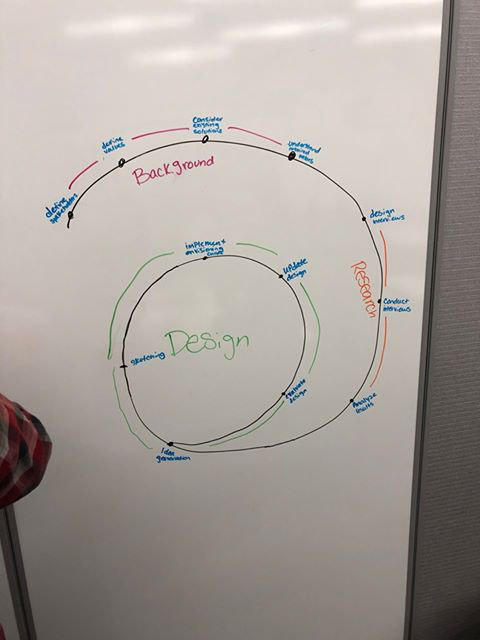

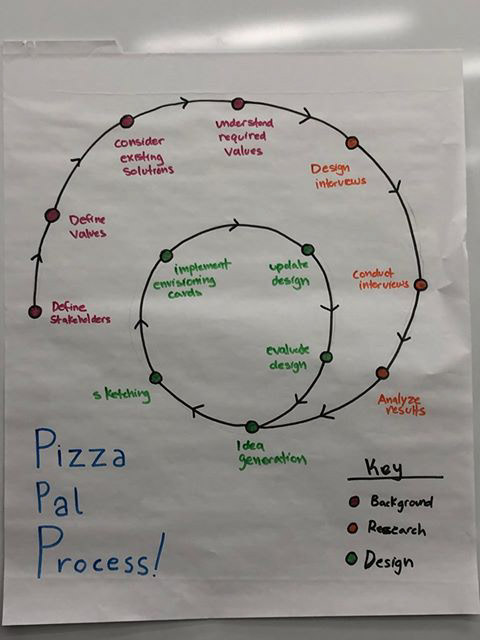

Initial Process Brainstorm

First Process Draft

Final Process

For this project, we identified 11 discrete steps we would follow, born out of the development of a process map. These steps encompass the VSD design methodology but also include more granular tasks and investigations. Steps 8-11 would be repeated as necessary.

1 - Define Stakeholders (Direct and Indirect)

Stakeholder identification yielded a variety of candidates for focus, but we settled on customers (those who order pizza - direct) and consumers (those who consume pizza - indirect).

2 - Define Stakeholder and Designer Values

Customers carry a number of values ranging from convenience and quality to affordability taste, while consumers are primarily concerned with taste and freshness. Designer values included health-consciousness and respect.

3 - Consider Existing Solutions

During this stage, we investigated and discussed existing solutions from Dominos and Papa John’s to identify commonalities and trends.

4 - Understand Project-Specific Required Values

During this step, we sought to understand and define libertarian paternalism and fun, the two required values to consider for the project.

5 - Generate Initial Design

Armed with an understanding of the values, stakeholders and current landscape, we began brainstorming and developed a list of ideas to potentially incorporate.

6 - Sketch

Next, we hand-sketched some of these ideas and talked through them, identifying those ideas that may not be a good fit and adding new ones.

7 - Utilize Envisioning Cards

To fill in the gaps in our thinking, we turned to the Envisioning Cards and explored alternate viewpoints and considerations. These cards provide springboards for value consideration and discussion, and proved critical to this project.

8 - Design Semi-Structured Interviews

Conducted in two rounds, we developed a series of questions for the first round centered on determining how well our stakeholders understood the required values. The second round was focused on testing our prototype.

9 - Conduct Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews were conducted with multiple stakeholder group members and shaped the design of our solution.

10 - Analyze Interview Results

As a team, we discussed the feedback from the interviews and agreed on how it would alter and inform our existing design.

11 - Revise Initial Design

The prototype design was updated to reflect the input from the stakeholder interviews.

Conceptual Investigation

Throughout this project, we focused on designing our app with the values of libertarian paternalism and fun in mind. In order for our pizza application to embody these values, we first explored the definitions of these terms and conducted analysis of both potential direct and indirect stakeholders. Afterward, we analyzed the values of our stakeholders based on assumptions and drew upon our own personal values and experiences as designers.

Before starting this project, we were given the definition of libertarian paternalism, which is defined as an approach addressing a complex web of values including freedom of choice, self-control, human welfare, and more. By breaking this definition down to its component parts, we see the inherent tension in the term - libertarian implies the freedom of choice by opting in or opting out while paternalism demonstrates an attempt to influence one’s choice for their own betterment. When combined, it encourages stakeholders to make a “good” choice with the help of mental nudges without eliminating the freedom to express their preferences.

In addition, we also define fun as an activity or interaction that provides a sense of joy and or excitement. As designers, we understand that the definition of fun is subjective and is different for everyone, so as a result, we looked from our own experiences of how fun has impacted us. Through our discussions, we agreed that fun was best spent through shared experiences with others. Whether that be a great pizza party with family, friends or pets, we want to deliver that experience. Ultimately, we define fun as motivation that will encourage our users to invest in the experiences they share with their pals, hence the name PizzaPals.

Stakeholders

Before immediately developing our design solution, we first identified our direct and indirect stakeholders. The primary stakeholders of our PizzaPals app would be the customers who directly interact with the app as they are the ones responsible for purchasing the pizza. As customers, they expect to communicate with friendly and reliable staff and consume pizza that not only tastes great, but is also safe to eat, is accurately made, and is affordable for the right price.

While all of these things do contribute to the overall convenience and satisfaction of the customers, many customers will still come with their own value tensions. for example, figuring out "what I want" versus "what I should have" can be a difficult decision for some customers. Some customers may value their calorie intake more than others. in addition, other customers may 5 value speed or a faster check-out rather than working with a paternalistic app that may require more attention to use.

Indirect stakeholders are those who do not directly use the app. Our primary indirect stakeholders would be the consumers, such as families and friends, who share in eating the pizza but may or may not be decision makers when ordering. With pizza being a usual dish for social gatherings, we can assume that our customers will come in all numbers, ranging from one individual to large group settings. Although consumers would not directly use the Pizza app, they are the ones who could potentially be impacted by the app the most. In general, consumers have similar values with the customers.

The next indirect stakeholders we considered were the business employees and company owners. Although they do not completely use the Pizza app for its intended purposes, they would indirectly use the app as a form of communication for mobile ordering. Just like the customers, employees and business owners also value quality. They are committed to providing satisfactory services that value friendliness, safety, accuracy, and efficiency. While their goal is to have the customers best interests in mind, there will be some value tensions to consider. For example, employees and business owners want to make a profit, but, at the same time, they want to ensure that the quality of food is of high enough quality to merit return business.

Finally, we also considered our suppliers as indirect stakeholders. As business partners, suppliers value profit and loyal relationships. Their relationships would be based on mutual respect and they would be just as motivated in providing quality products in order to continue making profit.

Empirical Investigation

Semi-Structured Exploratory Interviews

Before Conducting interviews, we developed a set of questions designed to gauge the level of understanding of the required values held by the stakeholders we had access to. 6 These questions included:

• Are you familiar with libertarian paternalism?

• Do you think it is appropriate for a company to give suggestions to you? Why or why not?

• Do you think it’s possible for a company to have your best interest in mind?

• Have you ever experienced a time where a company suggested something that you enjoyed?

• Is there a time where you didn’t appreciate a suggestion?

• Do you think it is appropriate for a company to give suggestions to you? Why or why not?

• Do you think it’s possible for a company to have your best interest in mind?

• Have you ever experienced a time where a company suggested something that you enjoyed?

• Is there a time where you didn’t appreciate a suggestion?

Findings from these interviews suggest that none of these individuals had ever been exposed to the term “libertarian paternalism”. Most tried to provide an educated guess and one simply answered no. Often their educated guess is not accurate.

For example, one interviewee stated that the word “libertarian” is synonymous with “progressive.” It appears they confused liberal with libertarian which in the United States is not interchangeable. Libertarians tend to advocate for less government intervention to allow for more free-will and self-control, which may at times overlap with a liberal worldview but not necessarily.

All interviewees, however, did understand the term paternalism as a concept that provides guidance and direction. They believed that it is appropriate to have companies give suggestions, but they all believed there should be limits and that often companies step over the line. They all agreed that the fact that intent to purchase something opens the door to these company’s suggestions. The consensus was when companies become too pushy, interviewees found them too intrusive.

Additionally, all interviewees agreed that some companies have your best interest in mind, but profit is always their number one interest and that can override the purchaser’s interest. These interviewees expressed that they had, however, had moments where they enjoyed a company’s suggestions. From samples at Costco to Netflix making movie recommendations, interviewees found these aspects positive as they saved time and/or money.

As for the format of the suggestions, all agreed that pop-up ads were not appreciated and often distracting. They also noted that ads that target the individual too specifically were violations of their privacy, with many of the interviewees preferring to have an opt in for the most aggressive ads.

It was clear from interviewing our stakeholders that all of them valued the use of subtle positive nudges and described intrusive nudges that a company would use as negative. This notion of “positive nudges” would become the foundation of our design based on the input we received from this process.

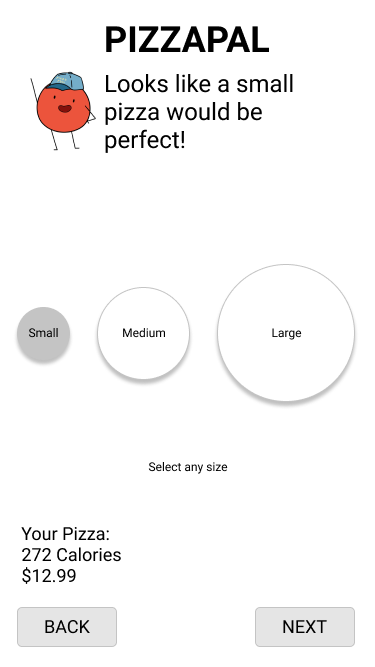

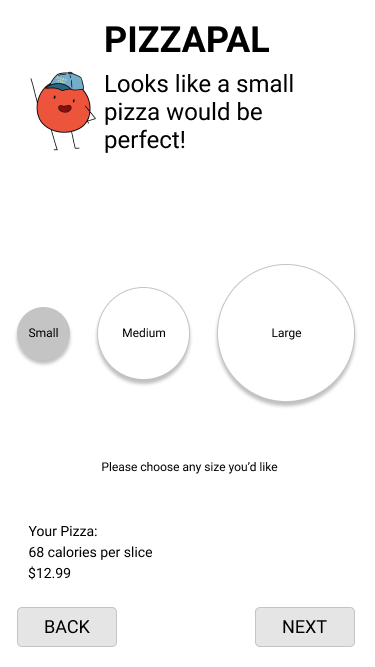

Usability Evaluation

For our user testing, we asked college students to be our participants. During the exercise, participants were asked to order a pizza using our prototype application. Each participant was able to easily navigate through the app; however, after they entered the number of people for whom they were ordering pizza, three of our participants were unaware the app had preselected the size of the pizza when they gave the number of people they were ordering for. At that point they were unsure what the next step was. This may speak more to the fidelity of the prototype than actual usability, but it was worth noting. One user suggested it be more apparent that the size was preselected and make it more apparent that you have the option to choose another size.

From this we learned that the wording of the ‘select any size’ under the display of the pizza sizes was not clear to the user. They were unaware they could opt out of the preselected size, which was based on the number of individuals they were ordering for and choose any size they wish to have. This feedback was incorporated into a revision of this portion of the application (Fig. 5), along with changes to the calorie count representation.

Original Pizza Size Interface

Revised Pizza Size Interface

Another user pointed out that our streak and calorie counts reflected in the app are not realistic for the user. Because the calorie count is based on the number of pizzas ordered and not the amount consumed, it gives the misconception that the caloric number is a lot higher than what each individual actually consumed if you are ordering pizza for multiple people. With this feedback, we recognized that we should change the wording from the number of pizzas consumed to the number ordered. This would give a more realistic view and not make the users feel ashamed of ordering multiple pizzas with their friends.

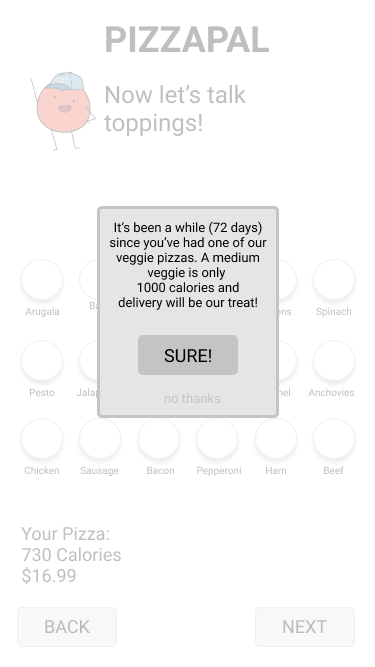

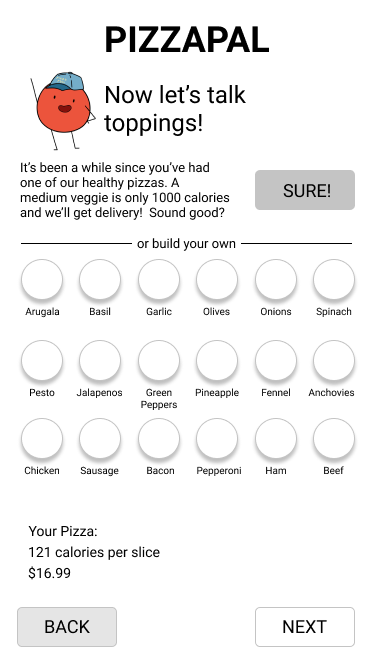

Based on our users understanding of libertarian paternalism, they expressed that they value positive nudges. One user pointed out that our feature of offering a veggie pizza with a large pop up window was not perceived as a positive nudge but rather felt intrusive. With this we learned that our users perceive subtle nudges as more positive but when it is a larger nudge it is perceived negatively. Based on this feedback, we removed the pop up and incorporated the positive nudge into the UI.

Prototypes

Initial Prototype

Revised Prototype

Technical Investigation

As a result of our conceptual and first empirical investigation, we found that overbearing paternalism was not ideal for the user experience. Ultimately, we decided to keep things simple and straight to the point; which is why we decided to adhere to a traditional mobile pizza ordering app to meet the needs of the stakeholders we know best. We used Figma as our main prototyping tool to demonstrate our solution for a pizza ordering app and within our solution, we focused on our goal of having an application that embodied the values of libertarian paternalism and fun. Based on our empirical investigation, we also wanted to present our users with subtle, positive nudges as a requirement. Through this prototype, our users would follow a sequence of basic tasks such as logging in, defining how many pizzas are needed, choosing the size, and choosing the toppings.

A key feature of our app is the “pizza streak.” The original goal for this screen was to showcase how much the customer has spent and consumed within a year. Inspired by SnapChat’s streak system of promoting continuous engagement, we wanted to slightly gamify our solution in order to motivate our users to buy pizza within a certain caloric level. However, unlike SnapChat, our streak system is not based on daily use, but rather whenever a user orders a healthier pizza. This more subtle solution encourages our users to make good choices and focus on healthier, long-term pizza consumption.

Positive nudges are also unique part of our solution. In general, positive nudges are more carefully worded and are intentionally designed not to discourage or shame the users for ordering specific items. For example, instead of saying “You’ve had meat-heavy pizzas lately. How about something lighter?”, we wanted to encourage our users by highlighting the positives by saying “It’s been awhile since you had a veggie pizza. A medium veggie pizza is only 1000 calories and delivery will be out treat!” or suggesting a vegetable topping after a meat topping is added.

Project Evaluation

Overall, the PizzaPals application included features that supported values of both libertarian paternalism and fun. Each feature that the team included was designed with the intention of being what we called a “positive nudge.” Based on the initial conceptual investigation, the team discovered a pattern in which many users found some nudges inspired a sense of shame or contempt, perhaps leaning too heavily on the paternalism half of libertarian paternalism. With this in mind, the team decided to only include positive and supportive suggestive features while discarding ones that could be considered shameful. This meant crafting lines for the app’s mascot, Pepper, that continued to remain positive even when a user made a choice that the designers might consider to be unhealthy.

For example, a user might tell PizzaPals that they are ordering pizza for 2 people which causes Pepper to suggest that they order a medium pizza. If a user then proceeds to order a large, Pepper will say “A large? Nice!” instead of “Are you sure you need a large?” Although this is a subtle difference, many users found it to be a significant change in the way they viewed the app. However, one user felt that having Pepper comment at all on the size change could still be taken as sarcastic or shame inducing. Given more time and research, the approach verbiage to use in this instance would be developed to avoid this effect.

A similar and perhaps more successful positive nudge was the healthy pizza streak feature that rewarded users for their healthy pizza behavior with free delivery rather than shame them for an unhealthy choice. The team felt that positive reinforcement was a more powerful tool in manipulating user behavior, especially after receiving supporting feedback while conducting inquiries.

In terms of fun, many users found Pepper to be the major source of personality and enjoyment while using the app which fulfilled a major goal of the team. However, one thing the team did not foresee was some users viewing Pepper as condescending or patronizing when he provides suggestions to the users, even when those suggestions were positive. One user even thought that PizzaPals was originally meant for children based on their interactions with Pepper. From this feedback, the team realized that they had managed to successfully include values of libertarian paternalism and fun but had made the mistake of underestimating their users in the process. What was supposed to be fun and endearing was sometimes seen as annoying and unnecessary.

From a “creepiness” standpoint, PizzaPals managed to maintain a playful tone that did not come across as knowing more than it should or violating the privacy of the user. This playful tone was mostly facilitated by the lines spoken by Pepper and by many of the included nudges relying on input directly taken from the user after the user is prompted rather than taken from data that is automatically tracked unbeknownst to the user.

PizzaPals needed to manage to be fun without being patronizing and paternal without being shameful. In the end, the app did a successful job maintaining the desired values although each came with its own set of tradeoffs that the team at times found hard to balance.

Lessons Learned

The main lessons that the team identified as having learned by applying value sensitive design methods to the PizzaPals process can be summarized as follows:

User Involvement

The inclusion of feedback from users was one of the most valuable steps in the design process. Two major points in the project process involved direct user feedback. The first point was during the conceptual inquiry phase in which the team asked users how well they understood the concept of libertarian paternalism while the second point was during the prototype phase in which the team conducted usability studies. Both these phases provided the team with surprisingly robust information that they otherwise would not have considered. Similarly, talking with users helped determine other values such as the inclusion of “positive nudges” rather than shameful suggestions as a method to support libertarian paternalism within the PizzaPals application.

Defining Values

As a result of both outside research and direct user feedback, the team found it very important to clearly identify and define the desired values of the project. This meant not only defining libertarian paternalism within the scope of the team, but also in understanding how users defined it. One thing we wished we would have done looking back on the process would have been including the value of fun throughout the contextual inquiry stage. Asking users how they defined fun may have provided better insight in how the PizzaPals application could support both values.

Making Assumptions

Because the team felt that they understand how users defined fun as a value, I implemented a healthy pizza streak feature and a mascot in order to support fun as a value. This assumption later proved to be a mistake after some users in the usability study revealed that they found the mascot to be sarcastic and patronizing rather than fun. Looking back, validating the assumption that a mascot feature is considered fun by the majority of users would have been beneficial.

Designing the Process

One of the first steps conducted by the team involved the creation and presentation of the design process that we planned to follow in creation of the PizzaPals application. This step ended up being one the most important high-level stages of the project and allowed the team to make sure the project flow was logical, efficient, and realistic within the time constraints. This stage also allowed me to identify next steps beyond the scope of the project.

Envisioning Cards

Our use of the Envisioning Cards consisted first in identifying, as a team, which cards would be appropriate for the project. We acknowledge that this may have introduced an implied bias 13 (choosing certain cards over others) but we strove to be as objective as possible when determining which cards to discuss.

All members of the team agreed that the Time-focused cards were the least applicable to our project, so they weren’t included at all in our discussion.

While we explored each of the remaining cards and their prompts, some yielded more discussion than others. For example, the Stakeholder card “Variation in Human Ability” led to a lengthy discussion about considering differently-abled stakeholder groups which echoed the goals supported by the Diverse Voices approach.

We began building immediately on the assumption that every user would be equally and fully-abled. Some ideas we generated to address this identified gap were a unique version of the app with larger text and UI elements for those with visual difficulties or trouble with fine motor skills. We also discussed a text-to-speech feature, though many cellphones include this functionality natively. Finally, we briefly discussed considerations for the colorblind, but our app doesn’t depend on color heavily as an identifier so while this consideration would be nice, it wouldn’t have as much impact as some of the other ideas.

Another card that prompted discussion was “Value Tensions,” which helped us identify the tensions that existed within our design, both by nature of the project - libertarian paternalism could be considered a value tension in and of itself - and in the choices we made. For example, our design includes a prompt during the pizza construction process that requires the user to agree to ordering a healthy pizza or cancel. Feedback from one stakeholder implied that this prompt “slowed them down,” which spoke to another value customers have, speed, clashing with the required libertarian paternalism value. Ultimately, the Envisioning Cards provided a source of rich discussion of the project and our understanding of it. While we didn’t explore all of the cards, and some of those we did more than others, it was a valuable use of our time.

Conclusions

This project was unique in that the values (libertarian paternalism and fun) driving the design weren’t derived solely from the stakeholders and were instead defined externally from any discovery process. This unique foundation framed the project as more of a puzzle and our team found it interesting and satisfying to try to develop a creative solution. Core to the project was how well we felt we could straddle the line between suggestion and direction which is really the fundamental tension inherent in libertarian paternalism. As a team we believed our first attempt was good, but user feedback served its purpose and informed appropriate revisions to our initial design.

Undertaking this process allowed the team to explore and develop facility with skills like prototyping and interviews, things any designer should feel comfortable with, and the project overall continued to build our confidence in our ability to understand a problem, embrace the constraints of the problem space and create a viable solution.

Overall, applying specific methods of the Value Sensitive Design process to the creation and design of the PizzaPals application succeeded in highlighting subtleties within the project scope that otherwise would have remained hidden to us. Through the inclusion of direct user input throughout multiple stages of the project, the team was able to successfully identify the concept of “positive nudges” as a way in which the PizzaPals app can support values of libertarian paternalism without seeming creepy or shaming the user. The use of wireframes and prototypes also allowed the design team to focus on creating an enthusiastic mascot that supported values of personalization, personification, and fun. Although the PizzaPals application never made it past the prototyping stage, continuing to iterate within the identified VSD process and revisiting concepts identified from the envisioning cards would be the next step in bringing the application to fruition. In the end, the team found the VSD process to be a valuable resource in not only identifying and supporting desired values, but also in determining when those values fail to be met.